The Power of Backcasting

/It was 1977 that Draper Kauffman visited The Learning Exchange, an organization a friend and I had founded. Draper was a futurist and when visiting Kansas City someone suggested he visit the Learning Exchange. We had several hours together sharing our thoughts about how unprepared students were to think about relevant futures for themselves. Draper had been with the Rand Corporation, a futures think tank. He was horrified by the gulf between what was being taught in schools and the world that was unfolding in which students would find themselves. Over dinner with Matt (Taylor) and me, Draper got to talking about how he learned to trick the mind into opening up and allowing itself to play with the future.

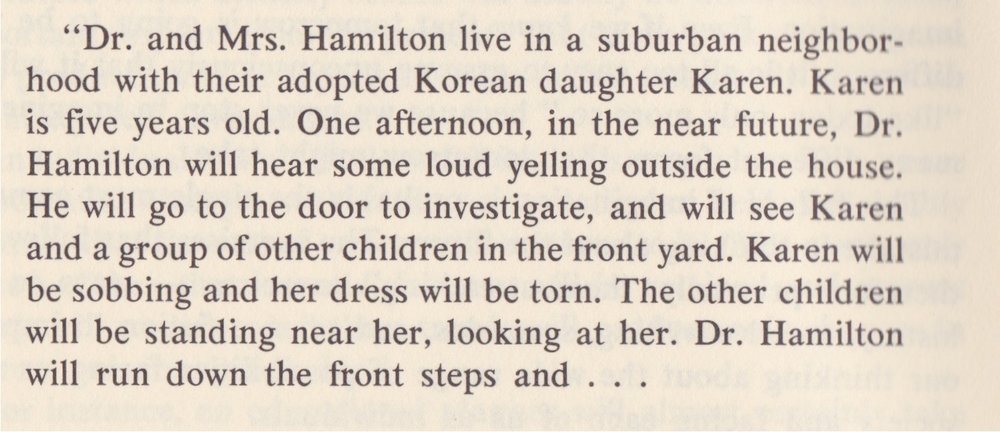

Draper left the Rand Corporation and secured his doctorate in education, specifically to teach teachers how to engage the future in grades K through 12. He had a hunch and he wanted to run experiments. When working with a classroom of 5th And 6th grade teachers, he handed out as assignment that simply ask the teachers to write the rest of the story. Each handout had a paragraph beginning the story. For all, the task was to make up a story based on this vague first paragraph. Draper left the classroom and retuned about 20 minutes later. Many of the teachers were just sitting, having written very little. Others were several pages into their story. He asked them to share their experience of writing. What none of them knew was that half the teacher’s paragraphs were written in past tense, the other half in future tense. With few exceptions, teachers who had past tense had fun and wrote many paragraphs making up the story as they went along. But those writing future tense struggled imagining a story that was yet to take place. This discovery led Draper to teach his course very differently.

Draper left the Rand Corporation and secured his doctorate in education, specifically to teach teachers how to engage the future in grades K through 12. He had a hunch and he wanted to run experiments. When working with a classroom of 5th And 6th grade teachers, he handed out as assignment that simply ask the teachers to write the rest of the story. Each handout had a paragraph beginning the story. For all, the task was to make up a story based on this vague first paragraph. Draper left the classroom and retuned about 20 minutes later. Many of the teachers were just sitting, having written very little. Others were several pages into their story. He asked them to share their experience of writing. What none of them knew was that half the teacher’s paragraphs were written in past tense, the other half in future tense. With few exceptions, teachers who had past tense had fun and wrote many paragraphs making up the story as they went along. But those writing future tense struggled imagining a story that was yet to take place. This discovery led Draper to teach his course very differently.

Draper began to teach modeling to his students. Most of them had no idea how to create models in their imagination… or how to use models in their thinking processes. To his students, the future was something left to the experts, to be proven right or wrong over time. The future was made up of facts just like in their history books, not possibilities and imagination.

Draper began to teach modeling to his students. Most of them had no idea how to create models in their imagination… or how to use models in their thinking processes. To his students, the future was something left to the experts, to be proven right or wrong over time. The future was made up of facts just like in their history books, not possibilities and imagination.

And it gave Matt and me an important insight. This is how the axiom "you can't get There from Here, but you can get Here from There" originated.

When you begin to frame the future from the present, all kinds of blocks show up. The present is full of the here and now and of many reasons change is not possible. Very little of our school life is composed for facilitating imagination and foresight. It is based on learning facts and facts are only within the past, or the here and now. It is based on test scores and right or wrong. To ease the tension, Matt and I decided that the first paragraph we wrote, from which participants would use as a baseline, would insure success. It would ask participants to remember their success story.

Draper's work was an important influencer in the development of our method and process. The importance of modeling, playing with ideas, assuming success became core principles in our work.

(Draper's book, Teaching the Future, is an important book and still very relevant. It is, however almost impossible to find. Our “Curriculum for the 21st Century” was also inspired by his work.)

This morning this article on Peter Drucker showed up in my in box. Drucker was quite good at envisioning THERE and bringing it to his HERE.

- Gail